Implementing Integrated Deterrence in the Cyber Domain: The Role of Lawyers

Remarks originally prepared and delivered by the Department of Defense General Counsel Caroline Krass at the U.S. Cyber Command Legal Conference in April 2023.

I. Introduction

Good morning. I want to thank General Nakasone and Colonel Hayden for inviting me to speak at the CYBERCOM legal conference today – I am delighted to be here. Every year, this conference gathers the legal community to explore the legal and policy aspects of military operations in cyberspace. This year’s theme of integrated deterrence is especially timely in light of current challenges we face as a Nation, the release last fall of the Biden Administration’s National Security Strategy, and the National Defense Strategy which nests within it. As the President explained in the 2022 NSS, we live in a “decisive decade,” marked by dramatic changes in technology, geopolitics, economics, and the environment.[1] In response, the Department of Defense has adopted a strategy to address this new reality and maintain our competitive advantage. The 2022 National Defense Strategy[2] sets forth the Department’s approach to advancing the defense of our Nation, paced to the growing multi-domain challenge posed by China. The NDS focuses on deterring strategic attacks and aggression while being prepared to prevail in conflict, if necessary.

A key component of the NDS is “integrated deterrence” – a holistic approach to addressing our competitors across domains, across DoD components and the U.S. Government, and with our Allies and partners around the world. In the current strategic environment, we see our competitors in cyberspace seeking to steal our technology, undermine our military advantages, threaten our critical infrastructure, disrupt our government and commerce, weaken our collective prosperity, and challenge our democratic processes. The scope, pace, and sophistication of this cyber activity continues to rise around the world. Under the framework of integrated deterrence, the Department is countering these malign cyber activities by taking action to generate insights about the adversary’s cyber operations and capabilities; enable the U.S. Government, industry, and international partners to create better cyber defenses; and act to deter or, when necessary, disrupt adversary cyber actors and halt malicious activities. Our success in the cyber domain depends on maintaining an ability to move quickly and cohesively with key partners within the U.S. Government and around the globe.[3]

The law is an integral component of furthering these strategic objectives. Today, I will elaborate on the role of the lawyer in advancing integrated deterrence, with a focus on the cyber domain. Lawyers are essential to successfully achieving integrated deterrence. And DoD lawyers have a profound obligation to ensure that the Department’s activities are conducted consistent with applicable domestic and international law. A key priority for my office is ensuring not only that we follow the rule of law in our own work, but also that we, as a Department, promote the rule of law around the world. Working with our Allies and partners requires recognition that we might, at times, be subject to different legal obligations or adopt different interpretations of certain legal rules, while ensuring we remain aligned on core issues wherever possible.

Determining the shape and contours of domestic and international law raises challenging questions that we wrestle with as an international legal community, which includes our civilian lawyers and judge advocates across the U.S. Government; legal advisers for our Allies and partners; and civil society, including academics and non-governmental organizations. Today, I will highlight some of those challenging questions and how we are thinking about them, specifically focusing on evaluating cyber operations against the international law framework of prohibited intervention and countermeasures, as well as the First and Fourth Amendments of the U.S. Constitution.

II. Integrated Deterrence and the Role of Lawyers

Before I dive into how lawyers help further integrated deterrence in the cyber realm, I’d like to spend a few moments on what “integrated deterrence” means. The 2022 NDS defines integrated deterrence as: “using every tool at the Department’s disposal, in close collaboration with our counterparts across the U.S. Government and with Allies and partners, to ensure that potential foes understand the folly of aggression.”[4]

My colleague, Dr. Colin Kahl, Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, has explained that integrated deterrence is a reminder that successful deterrence must seamlessly incorporate tools from every domain, including, of course, cyber and space; from every geographic theater; and from multiple instruments of national power, including not only military activities but also diplomacy, economic tools, and others. Integrated deterrence spans the spectrum of competition and armed conflict – to include gray zone activities – and immeasurably benefits from the critical assistance of our Allies and partners.[5] The ultimate goal is a comprehensive approach to deterring conflict and, should it arise, keeping such conflict at the lowest possible level. This is particularly important when nuclear powers are involved.[6]

Three key ways in which the United States enhances integrated deterrence are: (1) escalation management;[7] (2) campaigning; and (3) prioritizing interoperability with our Allies and partners.[8] In recent years, the cyber domain has taken on greater importance in each of these areas. Law, of course, plays an essential role as well. As lawyers, mastering a deep understanding of the relevant international and domestic legal guideposts enables us to explain to policymakers the full menu of legally available policy options.

The first concept, escalation management, is inherently linked with deterrence. State activities in the cyber domain have the potential to lead to inadvertent escalation, especially where there are insufficient “collective experience, common understanding[] and established norms of behavior”[9] to allow competitors to correctly interpret intent. Against this backdrop, lawyers have an opportunity to support integrated deterrence by clearly articulating legal standards; working alongside policymakers to develop and implement norms of responsible behavior; and helping to provide a vocabulary for States to communicate expectations and redlines, all with the objective of adding a measure of predictability to cyber-related interactions between State actors. Legal practitioners play an important role in ensuring that States do not misinterpret actions in cyberspace and thus risk inadvertent escalation.

Another way in which the United States enhances integrated deterrence is through campaigning. The NDS defines campaigning as “the conduct and sequencing of logically-linked military activities to achieve strategy-aligned objectives over time.”[10] Campaigning is a daily effort to close warfighting vulnerabilities, shape the perceptions of our competitors, and sow doubt that they can achieve their objectives through directly countering the United States, our Allies, or our partners.[11] In the cyber domain, campaigning occurs through day-to-day contact with our competitors.[12] It includes operations to “degrade competitors’ malicious cyber activity and to prepare cyber capabilities to be used in crisis or conflict.”[13] And it happens primarily in the gray zone – that is, on the spectrum of competition below the level of or outside the context of armed conflict. Here, too, we as lawyers play an important role in advising on the types of activities that might cross thresholds in international law, such as whether an activity could constitute a prohibited intervention or a use of force. Ensuring our planners understand applicable legal rules can facilitate the development and deployment of complex and enduring campaigns.

Finally, the United States enhances integrated deterrence through interoperability with our Allies and partners, which enables us to work together as one team. Some of our Allies, like the United Kingdom and Japan, have adopted strategies which include elements similar to our National Defense Strategy’s approach to integrated deterrence. Interoperability with our Allies and partners is particularly relevant in the cyber domain, in which technology transcends territorial boundaries and effortlessly brings us into contact with others around the world. To operate most effectively with our Allies and partners, it is important to have common understandings of the respective legal frameworks governing our actions in cyber.

Lawyers have already played a vital role here. States now generally agree that international law applies in cyberspace[14] and, along with NGOs, civil society, and academia, States have made tremendous progress in clarifying how various aspects of international law apply to cyber operations. And dialogue continues regarding how particular rules of international law apply to specific scenarios in cyberspace. There is always room to create more commonality, and thus enhance integrated deterrence.

III. Importance of International Law

Our clients fully embrace the importance of adhering to international law. One of the key precepts of the 2022 National Defense Strategy is the promotion of a rules-based international order. International law is the framework that States have adopted to set binding standards for their behavior, serving as an essential pillar of stability and order in the international system. States have committed to abide by international law not only in their interactions with each other, but also, in many respects, in their treatment of their nationals and others within their territory and subject to their jurisdiction. International law can provide the guideposts States use both to criticize unlawful conduct and to respond together.

The United States believes that our compliance with international law in the cyber domain is a foundation for the legitimacy of our military operations. As former State Department Legal Adviser Harold Koh presciently said over a decade ago at one of the first CYBERCOM legal conferences, where he clearly set forth the U.S. government view that international law applies in cyberspace, “if we succeed in promoting a culture of compliance, we will reap the benefits. And if we earn a reputation for compliance, the actions we do take will earn enhanced legitimacy worldwide for their adherence to the rule of law.”[15]

Clarity, predictability, and shared understandings of the law play the same important role for deterrence in the cyber domain as they do in other areas of State conduct, whether in competition or in conflict. But, in contrast to many other areas of State activity, outsiders are rarely able to observe State cyber behavior directly. As a result, the cyber domain often affords minimal public visibility into the two preconditions for establishing customary international law: general and consistent State practice and opinio juris,[16] which are statements affirming that a State is acting out of a sense of legal obligation. As a result, there is heightened value in States continuing the public conversation regarding how specific rules of international law – whether established in treaty or by custom – apply in cyberspace, and publicly identifying violations when they occur. Increased transparency enhances legitimacy and predictability by helping to develop and strengthen expectations surrounding State behavior, as well as possible responses, in the rapidly evolving cyber domain.

We therefore must continue to recognize the applicability of international law to State activity in cyberspace during both peacetime competition and armed conflict, and we must continue to develop our understanding of how it applies to the conduct of military operations. The United States has previously articulated certain aspects of our interpretation of international law in the cyber domain. For example, we have affirmed that a State’s inherent right of self-defense, recognized in Article 51 of the U.N. Charter, may in certain circumstances be triggered by cyber activities that amount to an actual or imminent armed attack.[17] And we have affirmed that States conducting activities in cyberspace must take into account the sovereignty of other States, including outside the context of armed conflict.[18]

One important, though sometimes overlooked, method for advancing the conversation regarding specific rules of international law is to raise questions for discussion. By asking those questions, States can identify areas where the particular application of the law is less clear. The purpose of identifying these unanswered or underexplored issues is to prompt the entire legal community, as well as policymakers, to consider and work towards resolution of these questions.

Over the balance of my remarks, I will focus on summarizing the current state of the law in two important areas of the international legal architecture below the threshold of armed conflict – prohibited intervention and countermeasures – and then identify several questions that remain the subject of discussion and debate regarding the application of those legal concepts in the cyber domain. I will conclude with an explanation of how our military operations in cyberspace are conducted consistent with the First and Fourth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. My goal is to advance the public conversation about and understandings of these rules, thereby contributing to the advancement of integrated deterrence, as set forth in the National Defense Strategy.

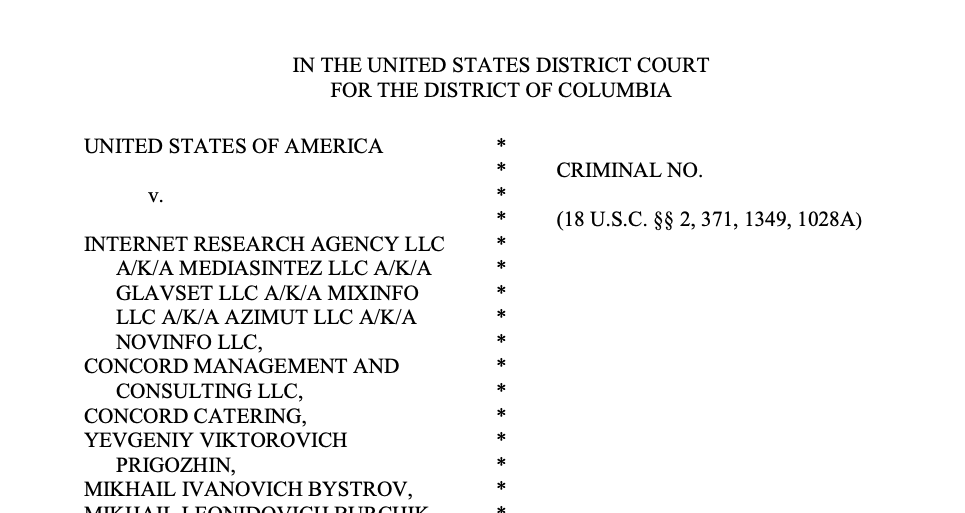

a. Prohibited Intervention

I’ll begin with the customary international law rule of prohibited intervention, a concept that is also reflected in certain treaties that the United States has joined.[19] As the International Court of Justice, or ICJ, described in its merits judgment in the Case Concerning Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua, the rule of prohibited intervention forbids States from engaging in coercive action that bears on a matter that each State is entitled, by the principle of State sovereignty, to decide freely.[20] Prohibited intervention thus plays an important role in protecting State sovereignty and preventing interstate disputes – contributing directly to the goals of integrated deterrence.

Although the scope of prohibited intervention is generally understood to be relatively narrow, certain peacetime activities of States in cyberspace could run afoul of this high threshold.[21] The United States has previously said, for example, that a cyber operation by a state that interferes with another country’s ability to hold an election, or that manipulates another country’s election results, would violate the rule of non-intervention.[22]

It is widely recognized that prohibited intervention includes two elements: (1) the action must interfere in the matters the targeted State is permitted to decide freely under the principle of sovereignty; and (2) it must be coercive. However, the precise meaning and contours of these elements are not well-defined – and cyberspace magnifies these already existing uncertainties. Working with our Allies and partners, and appreciating contributions from civil society and academia, to advance the understanding of these fundamental concepts can contribute to the broader goal of a shared and more nuanced view of how international law applies in cyberspace.

i. Domaine Réservé

Let me start with which matters a State is permitted to decide freely under the principle of sovereignty. Many commentators refer to these matters as a State’s “domaine réservé” – or “reserved domain” in English. Although the United States does not publicly use that phrase in formal writings, I’ll use it today as a convenient shorthand in describing past and current discussions on this topic.

As the ICJ said in the Nicaragua merits judgment mentioned earlier, one matter within the domaine réservé is “the choice of a political, economic, social and cultural system, and the formulation of foreign policy.”[23] Although the ICJ expressly limited its discussion to those aspects of prohibited intervention that it considered most relevant to the resolution of the dispute in that case,[24] one abiding question is: how can we better understand the contours of which activities are matters a State is permitted by the principle of state sovereignty to decide freely?

The term domaine réservé appeared in an advisory opinion of the Permanent Court of International Justice – the precursor to the ICJ. In that opinion, the PCIJ was assessing the scope of a dispute resolution provision of the Covenant of the League of Nations, which did not apply to disputes arising out of matters solely within the domestic jurisdiction of a State. In assessing the legality of French decrees imposing French nationality on all persons born in Tunis and Morocco – which had the effect of converting British subjects born in the French zone into French nationals – the PCIJ used the term domaine réservé to capture matters of a State’s affairs that are solely within the jurisdiction of a State. The PCIJ noted that some matters – such as, in principle, nationality – are not governed by international law and thus part of a State’s reserved domain.[25] The Court observed that the parameters of the domaine réservé will evolve over time, because whether a certain matter is solely within a State’s domestic jurisdiction was a relative question that would depend on a State’s obligations to other States and the development of international relations.

The PCIJ was not addressing the prohibition against intervention, and its remarks do not govern that distinct issue. But this history may help give a sense of what some people have in mind when they refer to the domaine réservé.

In today’s interconnected world, having a sharper understanding of the parameters of matters a State is permitted, by the principle of state sovereignty, to decide freely could contribute to clarity and predictability. Against this backdrop, a number of States in recent years have begun to explore how the concept of prohibited intervention applies in cyberspace. They have identified additional areas that, in their view, fall within a State’s domaine réservé for purposes of prohibited intervention, including elections and, more recently, healthcare. For example, last year the United Kingdom identified domestic healthcare, financial markets, energy supply, and elections as falling within its domaine réservé for the purposes of prohibited intervention.[26] The United States in 2021 identified manipulation of a State’s election results, or coercive interference in a State’s ability to hold an election or to protect the health of its population, as potentially constituting violations of the rule.[27] In this respect, certain aspects of a State’s provision of healthcare could be part of its domaine réservé, whether administered by the State or predominantly through the private sector. Italy and New Zealand have also suggested that coercive interference in healthcare could violate the rule on prohibited intervention.[28]

As States consider how to develop their thinking further on the domaine réservé as understood for purposes of prohibited intervention, some may look to historical sources. For example, in its Nicaragua judgment, the ICJ looked in part to the 1933 Montevideo Convention – to which both Nicaragua and the United States were parties. The Montevideo Convention provides that each party to that treaty has the right “to organize itself as it sees fit, to legislate upon its interests, administer its services, and to define the jurisdiction and competence of its courts.”[29]

At the same time, and as the PCIJ observed, States will want to bear in mind that the parameters of a State’s domaine réservé will depend in part on its obligations to other States, which can develop over time. To give one example of particular importance in the cyber context, by becoming parties to the United Nations Charter, all States today have agreed that certain matters are unquestionably matters of international concern that may be regulated by international law, such as the prohibition on the use of force in Article 2(4). Articles 1(3), 55, and 56 of the Charter each commit U.N. Member States to respecting international human rights. This, in turn, has led to the development of human rights treaties. States that are parties to such treaties have consented to legally binding obligations aimed at protecting specific human rights, such as freedom of expression, freedom of association, and the freedom of religion or belief. Under this international human rights regime, excessive regulation of online content, including censorship and access restrictions, cannot be justified as a sovereign prerogative.[30] And as the United States has reaffirmed, “any regulation by a State of matters within its territory, including use of and access to the Internet, must comply with that State’s applicable obligations under international human rights law.”[31]

ii. Coercion

Having explored the matters a State is permitted by the principle of state sovereignty to decide freely, I turn now to the second element of prohibited intervention: the activities must be coercive. While coercion can mean different things in different contexts, the scope of coercion for purposes of prohibited intervention remains particularly undertheorized and underdeveloped. It is well-established that a use of force against another State would be coercive.[32] On the other end of the spectrum, actions to which a State voluntarily consents, such as by the participation in human rights treaties just discussed, are, inherently, not coercive.[33] So where, on the spectrum between voluntarily-consented-to behavior and a use of force, does coercion begin?

The threshold for assessing an act as coercive in the context of prohibited intervention seems to be most clearly satisfied when a State has in fact been compelled to take, or refrain from taking, a particular course of action.[34] For example, a cyber operation that “manipulates another country’s election results” or “interferes with another country’s ability to hold an election” is coercive.[35] Certain cyber operations that prevent a State from protecting the health of its population could also be coercive.[36]

Because relatively few States have made public statements regarding their interpretation of the coercion element of prohibited intervention in the cyber domain, opinio juris on this matter is still developing. Many questions remain ripe for further examination.

One question relates to the degree of severity required for an act to be coercive. Although some may assume that a coercive action must involve force – because, of course, force is inherently coercive – such an interpretation is unduly limited. The prohibition against intervention makes sense as a standalone rule under international law only if it is distinct from the prohibition on the use of force, which means coercion for purposes of prohibited intervention in the cyber domain must include at least some acts below the threshold of a use of force.

Another question focuses on the intended consequences of a potentially coercive act. Is coercion, for purposes of prohibited intervention in the cyber domain, limited to those instances where the act is designed to compel a target State to undertake a specific act or omission? Some States support that approach.[37] Other States have adopted a broader view, that any act that deprives a State of freedom of control over elements of its domaine réservé would constitute prohibited intervention.[38] This broader approach may stem from a desire to hold States accountable for seriously disruptive conduct without requiring a target State to show that the conduct was meant to induce a particular act or omission. But focusing solely on deprivation of control, without more, could turn any disruptive cyber activity by a State that affects, even unwittingly, certain elements of another State’s activities into an unlawful intervention.

A final question for further exploration is whether coercion must succeed for the act to violate the prohibition on intervention. The ICJ’s Nicaragua merits judgment describes intervention as wrongful when done by “methods of coercion”[39] but does not address whether the method of coercion must be effective. Requiring coercion to actually produce the desired effect could have paradoxical results. It may disadvantage States that are better able to deflect or endure coercive acts because their resilience would foreclose a determination of prohibited intervention. And it could reward States whose attempted intervention fails. It could also mean the same act, directed towards two different States, could be a prohibited intervention against one State but not the other, depending only on attributes of the target State, for example, whether a target State’s cyber defenses were advanced enough to withstand the act. Such an outcome could impede the ability of States with more robust and resilient defenses to call out violations and, if desired and appropriate, to respond lawfully with countermeasures or other tools of international law.

b. Countermeasures

Before turning to domestic law, I’ll briefly address another topic that comes up frequently and raises challenging questions when discussing cyber operations in an environment of competition below the threshold of armed conflict: countermeasures. A countermeasure is an act that would otherwise be internationally wrongful but for the fact that it is taken in response to an internationally wrongful act attributable to a State.[40] Like international law writ large, the doctrine of countermeasures applies to state conduct in cyberspace and is an important tool for States that are victims of violations of international law – including, potentially, as a response to a violation of the rule of non-intervention. Indeed, as the United States has previously affirmed, a State injured by another State’s cyber activities that constitute an internationally wrongful act, but do not amount to an armed attack, may respond with non-forcible countermeasures in the cyber or any other domain.[41]

As in other domains, the lawful use of countermeasures in the context of peacetime cyberspace activities has several requirements. First, the countermeasure must be taken in response to an internationally wrongful act attributable to a State.[42] This factor reaffirms the importance of resolving the earlier discussion of prohibited intervention – particularly whether an attempted but unsuccessful intervention by coercion constitutes an internationally wrongful act.

Second, the countermeasure must be taken against the responsible State for the purpose of inducing that State to return to compliance with international law.[43] Third, the countermeasure must meet the requirement of proportionality and must be suspended without undue delay if the internationally wrongful act has ceased.[44] In the United States’ view, whether a measure is proportionate should be measured in relation to what is necessary to induce the breaching State to cease its wrongful conduct, as well as in relation to the size or gravity of the original breach itself.[45] In addition, countermeasures are generally understood to be temporary measures and should therefore be reversible to the extent possible.[46]

Finally, as a general rule, an injured State preparing to take a countermeasure in response to an internationally wrongful act in cyberspace attributable to another State must call upon the responsible State to cease its wrongful conduct, unless the need to preserve the injured State’s rights demands urgent countermeasures.[47] The purpose of this requirement is to provide the responsible State with notice of the injured State’s claim and the opportunity to respond or cease its wrongful conduct. But in practice, such notification in the cyber domain calls for further exploration.

For instance, what if notification and demand for cessation of another State’s internationally wrongful act would compromise a cyber operation that would be urgently executed as a lawful countermeasure? In that case, it is possible that the need to preserve the injured State’s rights would justify taking action without prior notification. Similarly, what if notification and a demand for cessation would tip off the offending State that a clandestine cyber operation will follow if that State does not cease its activities?

In addition, can the doctrine of countermeasures have any applicability to assist a State that has been a victim of a cyber operation that has been completed and is irreversible? Suppose the internationally wrongful act in which a State has engaged involves “hack and leak” activities. How could a demand for cessation, or a resort to countermeasures, bring the responsible State back into compliance once the “hack and leak” aspect of the internationally wrongful act is complete, because the leak cannot be reversed? It would seem relevant to this analysis whether there is also the expectation of further internationally wrongful acts occurring.

The doctrines of prohibited intervention and countermeasures are fundamental to peacetime stability and predictability in the international system, and, as the questions and discussion I offer today highlight, are ripe for further examination in the cyber context. By furthering these conversations, we as lawyers can make an important contribution to succeeding in competition and achieving integrated deterrence through the continued development of common understandings in the cyber domain.

IV. Domestic Law

I will turn now to a discussion of U.S. domestic law, focusing on military cyber operations against and affecting systems located outside the United States. The U.S. Constitution plays a significant role in safeguarding privacy and civil liberties, as DoD seeks to deter and protect against adversary “gray zone” activities in the cyber domain in a lawful and effective manner. As lawyers, we help our clients advance integrated deterrence and hold true to the Constitution by delineating the legal guideposts in domestic law, just as in international law. In the domestic law context, I will focus today on the First and Fourth Amendments.

a. First Amendment

The First Amendment is of course foundational in protecting free speech in the United States. As we combat efforts by our foreign adversaries to use disinformation and other influence operations in their attempts to further their own interests and to undermine our most cherished values, we must remain steadfast to the First Amendment as a critical touchstone.

Concerns about foreign influence in our political processes have existed since the founding of our Republic. We see this in the Constitution itself – for example, in the Emoluments Clause, which the Framers adopted “in order to protect U.S. officials from corruption and foreign influence.”[48] Combating malign foreign influence remains a key component of our national defense.

So, what role does the First Amendment play? Of course, the First Amendment protects Americans’ right to speak freely. The picture becomes more complicated when we look abroad, where foreign speakers generally have no First Amendment-protected right to speak.[49] This is certainly true of foreign States that wish to interfere in our electoral processes.

But the Supreme Court has also interpreted the First Amendment as protecting Americans’ right to “receive information and ideas, regardless of their social worth.”[50] This right to receive information encompasses, for example, the freedom to read and receive news and information about current events and other matters of public and private interest.

In several cases, the Supreme Court has recognized that Americans have a right to receive information from foreign speakers abroad, at least under some circumstances.[51] In a 1965 case called Lamont v. Postmaster General, for example, the Supreme Court struck down as unconstitutional a statute that required the postal service to hold “communist political propaganda” mailed to Americans from abroad and permitted release of that mail only upon affirmative request from the intended recipient.[52] And in a 1972 case called Kleindienst v. Mandel, the Supreme Court recognized that Americans’ First Amendment right to receive foreign information was implicated when the government precluded a Belgian citizen from traveling to the United States to deliver lectures.[53] These protections recognized by the Supreme Court are vitally important.

We must therefore carefully consider how to harmonize two interests – the right of the State to prevent foreign influence on government functions and the right of the individual to receive speech. For example, there may be some tension between Americans’ right to receive speech and the Nation’s interest in preventing foreign influence on U.S. elections. As legal practitioners charged with both defending the Nation and upholding the Constitution, we must navigate these issues. The First Amendment’s protections, including the right to receive speech, are rooted in a belief that robust political debate is essential for an informed electorate and a healthy democracy. At the same time, the protections of the First Amendment are not so expansive as to prevent the Nation from defending itself.

Accordingly, the analytical legal framework and case-specific evaluation of cyber operations require careful consideration of potentially competing interests, including the nature and strength of the governmental interest and the scope and tailoring of the impact a cyber operation may have on protected First Amendment rights. The role of the government lawyer in these circumstances is especially vital because such matters often will not be adjudicated by courts. It is incumbent on Executive Branch lawyers, then, to abide by the Constitution, respect civil liberties, and uphold the rule of law while protecting national security.

b. Fourth Amendment

I will now turn to the Fourth Amendment. In working to achieve integrated deterrence, it is advantageous to understand our adversaries’ plans, intentions, and capabilities. Accurate intelligence enables us to calibrate our deterrence efforts and integrate those efforts across domains and with Allies and partners. Today, cyber is a critical domain for gathering intelligence, and such intelligence is, in turn, vital to the development and conduct of cyber operations. Cyber operations also have the potential to lead to the incidental collection of intelligence to inform decisionmakers and future activities.

As we evaluate cyber operations from a legal perspective, sometimes the Fourth Amendment comes into play. The Fourth Amendment protects the “right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures” and limits the circumstances under which warrants can be issued.[54] Its basic purpose is to “safeguard the privacy and security of individuals against arbitrary invasions by governmental officials.”[55]

Core Fourth Amendment principles guide our cyber operations. For example, the Fourth Amendment protects U.S. persons whether they are in the United States or abroad and generally protects other persons located in the United States. Much like the First Amendment, however, non-U.S. persons located outside the United States generally will not be protected under the Fourth Amendment.[56] Cyber operations targeting such persons overseas therefore generally do not implicate the targets’ Fourth Amendment rights – because those targets do not have any Fourth Amendment rights in the first place.

Why, then, am I talking about the Fourth Amendment?

In the globally interconnected cyber domain, there is sometimes a chance that activities targeting foreign adversaries will result in the incidental acquisition of, for example, communications in which a U.S. person is a party. When a cyber operation implicates the Fourth Amendment rights of U.S. persons, further analysis is required.

That brings me to our second principle. The Fourth Amendment prohibits “unreasonable” searches and seizures. In the domestic law enforcement context, a search generally must be conducted pursuant to a warrant issued upon probable cause.[57] But the ultimate touchstone of the Fourth Amendment is reasonableness[58] – and neither a warrant nor probable cause is an indispensable component of reasonableness in every circumstance.[59] In most cases, cyber operations targeting non-U.S. persons located outside the United States do not implicate the warrant requirement. The warrant requirement generally would not apply, for example, to such searches conducted abroad[60] or to otherwise lawful surveillance that targets persons lacking Fourth Amendment rights but incidentally acquiring the communications of a Fourth Amendment-protected person who was not targeted.[61]

Even in contexts that do not require a warrant, a search implicating the Fourth Amendment must satisfy the reasonableness requirement.[62] This entails a fact-sensitive evaluation of the totality of the circumstances, balancing an activity’s intrusion into protected privacy interests against “the degree to which that intrusion furthers the government’s legitimate interest.”[63] When cyber operations directed against foreign adversaries implicate the Fourth Amendment rights of, for example, U.S. persons, there will often be significant interests to balance on both sides.

Where a cyber operation targeting a foreign adversary implicates the Fourth Amendment because of incidental collection, two criteria will help guide our review. First, we look at whether our collection methods are adequately focused and controlled to produce the required intelligence without unnecessarily invading the privacy of persons protected by the Fourth Amendment. And second, we look at whether adequate precautions are taken to limit those invasions of privacy that do occur – an inquiry that can take into account post-collection procedures such as limitations on retention, dissemination, and querying.

Lawyers across the government, including in the Department of Defense, help their clients work through these types of questions every day. In doing so, we advance the government’s vital national security interests, safeguard Americans’ privacy and civil liberties, and ultimately support integrated deterrence.

V. Conclusion

In sum, government lawyers play an instrumental role on a daily basis in advancing integrated deterrence, including in the cyber domain. We do so not only by guiding policymakers on legally available options, but also by seeking to further the conversation on how relevant rules of international and domestic law apply in cyberspace. Clearer definitions can, in turn, serve as guideposts to policymakers, ensure our actions are consistent with our values, and help maintain our legitimacy on the international stage.

Thank you.

[1] White House, National Security Strategy at 6 (Oct. 12, 2022), https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/8-November-Combined-PDF-for-Upload.pdf.

[2] U.S. Dep’t. of Defense, National Defense Strategy of the United States of America (Oct. 27, 2022), https://media.defense.gov/2022/Oct/27/2003103845/-1/-1/1/2022-NATIONAL-DEFENSE-STRATEGY-NPR-MDR.PDF [hereinafter NDS].

[3] See Statement of Hon. Dr. John Plumb, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Space Policy, Testimony Before the House Armed Services Committee, Subcommittee on Cybersecurity, Innovative Technologies, and Information Systems (Apr. 5, 2022).

[4] NDS, supra note 2, at iv.

[5] Dr. Colin Kahl, Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, The 2022 National Defense Strategy: A Conversation with Colin Kahl, https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=dF8LxP8hPhw (Nov. 4, 2022) [hereinafter Kahl Remarks].

[6] Id.

[7] NDS, supra note 2, at 10.

[8] Id. at 14.

[9] Id. at 6.

[10] Id. at 12.

[11] Kahl Remarks, supra note 5.

[12] Id.

[13] NDS, supra note 2, at 12.

[14] Report of Group of Governmental Experts on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security, U.N. Doc. A/70/174 (July 22, 2015).

[15] Harold Hongju Koh, International Law in Cyberspace, 54 Harv. Int’l L. J. Online 1, 11 (2012).

[16] See Jurisdictional Immunities of the State (Germany v. Italy: Greece intervening), 2012 I.C.J. 99, 122 (Feb. 3) (“Jurisdictional Immunities of the State”) (“In particular . . . the existence of a rule of customary international law requires that there be ‘a settled practice’ together with opinio juris.”) (citing North Sea Continental Shelf (Federal Republic of Germany/Denmark; Federal Republic of Germany/Netherlands), 1969 I.C.J. 44, ¶ 77 (Feb. 20) (“North Sea Continental Shelf”)).

[17] U.S. Statement, Official Compendium of Voluntary National Contributions on the Subject of How International Law Applies to the Use of Information and Communications Technologies by States Submitted by Participating Governmental Experts in the Group of Governmental Experts on Advancing Responsible State Behaviour in Cyberspace in the Context of International Security Established Pursuant to General Assembly Resolution 73/266, U.N. Doc. A/76/136* at 137 (July 13, 2021) [hereinafter 2021 GGE Compendium].

[18] See U.S. Statement, 2021 GGE Compendium at 139 (“The United States believes that State sovereignty, among other long-standing international legal principles, must be taken into account in the conduct of activities in cyberspace. Whenever a State contemplates conducting activities in cyberspace, the equal sovereignty of other States needs to be considered”); see also Brian J. Egan, Legal Advisor, U.S. Dep’t of State, Remarks on International Law and Stability in Cyberspace at Berkeley Law School (Nov. 10, 2016); Koh, supra note 15, at 11.

[19] See, e.g., Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States, art. 3, 8, 11, Dec. 26, 1933, 165 L.N.T.S. 19 (“No state has the right to intervene in the internal or external affairs of another.”); see also Charter of the Organization of American States, art. 19, 3(e), 20, Dec. 13, 1951, 119 U.N.T.S. 3 (“No State or group of States has the right to intervene, directly or indirectly, for any reason whatever, in the internal or external affairs of any other State.”); Additional Protocol to Montevideo Convention Relative to Nonintervention, art. 1, Dec. 23, 1936, 51 Stat. 41 (“The High Contracting Parties declare inadmissible the intervention of any one of them, directly or indirectly, and for whatever reason, in the internal or external affairs of any other of the Parties.”).

[20] See Military and Paramilitary Activities in and Against Nicaragua (Nicar. v. U.S.), Judgment, 1986 I.C.J. 14, 108 (June 27) (“A prohibited intervention must accordingly be one bearing on matters in which each State is permitted, by the principle of State sovereignty, to decide freely. One of these is the choice of a political, economic, social and cultural system, and the formulation of foreign policy. Intervention is wrongful when it uses methods of coercion in regard to such choices, which must remain free ones.”).

[21] See U.S. Statement, 2021 GGE Compendium, supra note 17, at 140.

[22] Id. at 140; see also Egan, supra note 18 (“For example, a cyber operation by a State that interferes with another country’s ability to hold an election or that manipulates another country’s election results would be a clear violation of the rule of non-intervention.”).

[23] See Nicar. v. U.S., 1986 I.C.J. at 108.

[24] See Nicar. v. U.S., 1986 I.C.J. at 108.

[25] See Nationality Decrees Issued in Tunis and Morocco, advisory opinion, 1923 Permanent Court of International Justice (ser. B) no. 4, at 24 (Feb. 7, 1923) (discussing nationality as a matter which, in principle, is not regulated by international law and describing such matters as part of a domain reserved to States).

[26] See Suella Braverman, U.K. Attorney General, “International Law in Future Frontiers,” (May 19, 2022), https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/international-law-in-future-frontiers [hereinafter Braverman Speech].

[27] See U.S. Statement, 2021 GGE Compendium, supra note 17, at 140 (“For example, a cyber operation by a State that interferes with another country’s ability to hold an election or that manipulates another country’s election results would be a clear violation of the rule of non-intervention. Other States have made similar observations. Further, a cyber operation that attempts to interfere coercively with a State’s ability to protect the health of its population—for example, through vaccine research or running cyber-controlled ventilators within its territories during a pandemic—could be considered a violation of the rule of non-intervention.”).

[28] See Italy, 2021 GGE Compendium, supra note 17, “Italian Position Paper on ‘International Law and Cyberspace,’” at 5 (2021) (“Italy sees merit in continuing to deepen the study of possible violations of the principle of non-intervention in cyberspace. That is particularly the case with regard to influence activities aimed, for instance, at undermining a State’s ability to safeguard public health during a pandemic . . . .”); see also New Zealand, 2021 GGE Compendium, supra note 17, “The Application of International Law to State Activity in Cyberspace,” para. 10 (2020) (“Examples of malicious cyber activity that might violate the non-intervention rule include . . . any cyber activity deliberately causing significant damage to, or loss of functionality in, a state’s critical infrastructure, including – for example – its healthcare system, financial system, or its electricity or telecommunications network). For a comprehensive collection of such statements, see the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research Cyber Policy Portal database at https://database.cyberpolicyportal.org/en/ or the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence Cyber Law Toolkit, which permits searches of national positions by issue, at https://cyberlaw.ccdcoe.org/wiki/Category:National_position.

[29] Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States, supra note 19, art. 3 (“Even before recognition the state has the right to defend its integrity and independence, to provide for its conservation and prosperity, and consequently to organize itself as it sees fit, to legislate upon its interests, administer its services, and to define the jurisdiction and competence of its courts.”).

[30] See Egan, supra note 18.

[31] Egan, supra note 18.

[32] See Nicar. v. U.S, 1986 I.C.J. at 108 (“The element of coercion, which defines, and indeed forms the very essence of, prohibited intervention, is particularly obvious in the case of an intervention which uses force, either in the direct form of military action – or in the indirect form of support for subversive or terrorist armed activities within another State.”).

[33] See Paul C. Ney, General Counsel, U.S. Dep’t of Defense, Remarks at U.S. Cyber Command Legal Conference (Mar. 2, 2020). In this regard, the principle of non-intervention is consistent with the basic international law principle of consent, under which “consent by a State to particular conduct by another State precludes the wrongfulness of that act in relation to the consenting State, provided the consent is valid and to the extent that the conduct remains within the limits of the consent given.” U.N. International Law Commission, Draft Articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts, with commentaries, art. 20(1) (2001) [hereinafter Draft Articles with commentaries].

[34] See Declaration on Principles of International Law Concerning Friendly Relations and Co-operation Among States, G.A. Res. 2625 (XXV), U.N. Doc. A/RES/2625 (XXV) (Oct. 24, 1970) (“No State may . . . coerce another State in order to obtain from it the subordination of the exercise of its sovereign rights or to secure from it advantages of any kind.”); see also Draft Articles with commentaries, supra note 33, art. 18(2) (In describing coercion for purposes of assessing whether a State that coerces another State to commit an internationally wrongful act is responsible for that act, stating that “[n]othing less than conduct which forces the will of the coerced State will suffice, giving it no effective choice but to comply with the wishes of the coercing state. It is not sufficient that compliance with the obligation is made more difficult or onerous . . . .”).

[35] Egan, supra note 18.

[36] See U.S. Statement, 2021 GGE Compendium, supra note 17, at 140 (“Further, a cyber operation that attempts to interfere coercively with a State’s ability to protect the health of its population–for example, through vaccine research or running cyber-controlled ventilators within its territories during a pandemic–could be considered a violation of the rule of non-intervention.”).

[37] See, e.g., Canada 2022 (prohibited intervention must include activities that “cause coercive effects that deprive, compel, or impose an outcome on the affected State on matters in which it has free choice”); Poland 2022 (“A cyber operation that adversely affects the functioning and security of the political, economic, military or social system of a state, potentially leading to the state’s conduct that would not occur otherwise, may be considered a prohibited intervention”); Estonia 2021 (“If an operation attributable to another state affects a state’s internal or external affairs in such a manner that it coerces a state to take a course of action it would not voluntarily seek, it would constitute a prohibited intervention”); Norway 2021 (“Cyber operations that compel the target State to take a course of action, whether by act or omission, in a way that it would not otherwise voluntarily have pursued (coercion) in matters relating to its internal or external affairs (domaine reserve), will constitute an intervention in violation of international law”); Singapore 2021 (stating “cyber-attacks against our infrastructure in an attempt to coerce our government to take or forbear a certain course of action on a matter ordinarily with its sovereign prerogative” constitute prohibited intervention); Netherlands 2019 (“The goal of the intervention must be to effect change in the behavior of the target state”). All of these statements are available through the CCDCOE Cyber Law Toolkit at https://cyberlaw.ccdcoe.org/wiki/Prohibition_of_intervention.

[38] See Braverman Speech, supra note 26 (“Some have characterised coercion as forcing a State to act differently from how it otherwise would – that is, compelling it into a specific act or omission . . . . But I want to be clear today that coercion can be broader than this. In essence, an intervention in the affairs of another State will be unlawful if it is forcible, dictatorial, or otherwise coercive, depriving a State of its freedom of control over matters which it is permitted to decide freely by the principle of State sovereignty.”); see also Government of Australia, 2021 GGE Compendium, supra note 17, at 5 (“A prohibited intervention is one that interferes by coercive means, either directly or indirectly, in matters that a State is permitted by the principle of State sovereignty to decide freely. Such matters include a State’s economic, political, social and cultural systems and foreign policy. Coercive means are those that effectively deprive or are intended to deprive the State of the ability to control, decide upon or govern matters of an inherently sovereign nature.”).

[39] Nicar. v. U.S., 1986 I.C.J. para. 205.

[40] See U.S. Statement, 2021 GGE Compendium, supra note 17, at 142; cf. Draft Articles with commentaries, supra note 33, art. 22(2) (“In the Gabčikovo-Nagymaros Project case, [the] ICJ clearly accepted that countermeasures might justify otherwise unlawful conduct ‘taken in response to a previous internationally wrongful act of another State and . . . directed against that State,’ provided certain conditions are met.”); Gabčikovo-Nagymaros Project, 1997 I.C.J. 7, ¶ 83 (Sept. 25).

[41] See, e.g., U.S. Statement, 2021 GGE Compendium supra note 17, at 142 (“In certain circumstances, a State injured by cyber activities that are attributable to another State and that constitute an internationally wrongful act, but do not amount to an armed attack, may respond with non-forcible countermeasures.”).

[42] See Draft Articles with commentaries, supra note 33, art. 22.

[43] See Egan, supra note 18, at 21; see also U.S. Statement, 2021 GGE Compendium, supra note 17, at 142; cf. Draft Articles with commentaries, supra note 33, art. 49 (“Countermeasures may only be taken by an injured State in order to induce the responsible State to comply with its obligations under Part Two, namely, to cease the internationally wrongful conduct, if it is continuing, and to provide reparation to the injured State.”).

[44] See Egan, supra note 18, at 21–22; see also U.S. Statement, 2021 GGE Compendium, supra note 17, at 142 (“Such countermeasures must be directed only at the State responsible for the wrongful act, must meet the requirements of necessity and proportionality, must be designed to induce the State to return to compliance with its international obligations, and, under the customary international law of State responsibility, must be suspended without undue delay if the internationally wrongful act has ceased.”).

[45] See Draft Articles on State Responsibility: Comments of the Government of the United States of America, March 1, 2001, reprinted in 2001 Digest of United States Practice in International Law, pp. 367–69.

[46] See Gabčikovo-Nagymaros Project, 1997 I.C.J. para. 87 (noting the requirement that the “purpose [of a countermeasure] must be to induce the wrongdoing State to comply with its obligations under international law, and that the measure must therefore be reversible”); see also Draft Articles with commentaries, supra note 33, art. 49(9) (“The phrase ‘as far as possible’ in paragraph 3 indicates that if the injured State has a choice between a number of lawful and effective countermeasures, it should select one which permits the resumption of performance of the obligations suspended as a result of countermeasures.”).

[47] See Egan, supra note 18, at 22; see also Gabčikovo-Nagymaros Project, 1997 I.C.J. at ¶ 87; Draft Articles with commentaries, supra note 33, arts. 43(2), 52(2).

[48] See President Reagan’s Ability to Receive Retirement Benefits from the State of California, 5 Op. O.L.C. 187, 188 (1981) (quoting Governor Edmund Jennings Randolph at the Virginia Ratification Convention for the U.S. Constitution, 3 M. Farrand, Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, 327 (rev. ed. 1937, 1966 reprint)).

[49] See USAID v. Alliance for Open Soc’y Int’l, 140 S. Ct. 2082, 2086 (2020).

[50] Stanley v. Georgia, 394 U.S. 557, 564 (1969).

[51] See Kleindienst v. Mandel, 408 U.S. 753, 753–56 (1972); Lamont v. Postmaster General, 381 U.S. 301, 306–07 (1965).

[52] Lamont, 381 U.S. at 302–05.

[53] Mandel, 408 U.S. at 762–65.

[54] U.S. Const. amend. IV.

[55] Carpenter v. United States, 138 S. Ct. 2206, 2213 (2018) (quoting Camara v. Municipal Court of City and County of San Francisco, 387 U.S. 523, 528 (1967) (internal quotation marks omitted)).

[56] See USAID v. Alliance for Open Soc’y Int’l, 140 S. Ct. 2082, 2086 (2020); United States v. Verdugo-Urquidez, 494 U.S. 259, 261 (1990).

[57] See Riley v. California, 573 U.S. 373, 382 (2014).

[58] See id.

[59] Treasury Employees v. Von Raab, 489 U.S. 656, 665 (1989).

[60] United States v. Stokes, 726 F.3d 880, 891–93 (7th Cir. 2013); In re Terrorist Bombings, 552 F.3d 157, 167–71 (2d Cir. 2008).

[61] United States v. Hasbajrami, 945 F.3d 641, 662 (2d Cir. 2019); United States v. Mohamud, 843 F.3d 420, 440–41 (9th Cir. 2016); cf. United States v. Muhtorov, 20 F.4th 558, 598–600 (10th Cir. 2021) (finding a similar exception based on a combination of factors).

[62] Maryland v. King, 569 U.S. 435, 448 (2013).

[63] In re Certified Questions of Law, 858 F.3d 591, 607 (FISA Ct. Rev. 2016) (citing Wyoming v. Houghton, 526 U.S. 295, 300 (1999)).